The Ice Wine Cometh (eventually)

In the middle of the night, in the middle of winter, there’s a very special grape harvest happening…

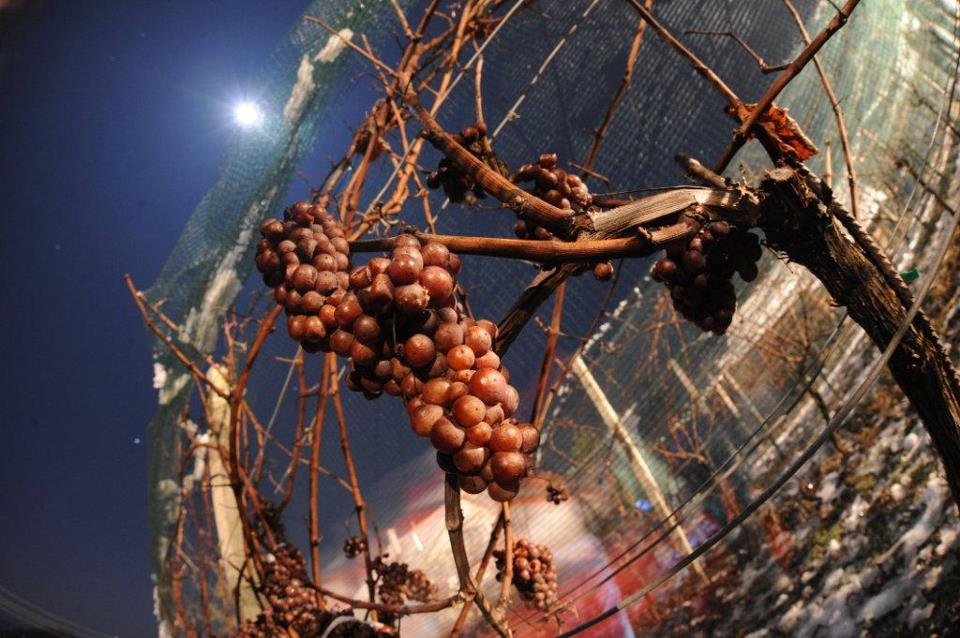

Winemaker Boris Drenški is up late into the night, checking his thermometer. He’s waiting for the temperature to drop below -7˚C (19.4°F) and hoping it will hit the -10˚C to -15˚C range. Then he will flick the switches on the floodlights to illuminate his vineyards. His grapes have been dangling there long after the leaves have fallen and four or five months after most other winemakers in Europe have harvested and vinified their grapes.

While other winemakers are tucked up in their warm beds, dreaming of filtering and bottling their 2014 vintages, Boris Drenški is warning his grape pickers of the dangers of frostbite.

Dressed like Arctic adventurers, they cut and drop the icy berries into plastic crates. It sounds like pebbles pouring into buckets.

Speed is of the essence now. The berries have to be processed before they thaw, as the whole purpose of leaving bunches on the vine to freeze is to sieve out most of the berries’ water as ice crystals and to discard these along with the seeds and grapeskins. All Boris is interested in is the thick, syrupy juice that is too rich in sugar and acid to freeze.

“These are the masochists of the wine world. In wine there may be truth; in ice wine there is definitely a blend of chapped lips, numb feet, sore joints, frozen fingertips, endless patience, high-risk and much frustration ”

Boris is one of the world’s top ice-wine makers. These are the masochists of the wine world. In wine there may be truth; in ice wine there is definitely a blend of chapped lips, numb feet, sore joints, frozen fingertips, endless patience, high-risk and much frustration. As if winemaking wasn’t hard enough, ice-wine makers push the limits to the extreme in pursuit of silky-sweet fruit flavours. Their grapes have to be in perfect condition leading into winter, so they have to cut and discard any unhealthy bunches during the summer and autumn. The healthy bunches are then left to shrivel and dehydrate, while the weather deteriorates and the grapes’ sugars, acids and fruit essences concentrate. As the only fruit left when the air turns frigid, it has to be protected from hungry birds and other animals by expensive netting. The grapes have to remain on the vine until they freeze, which is usually in the middle of the night at the end of January (but could be as late as February). While they hang exposed, there is always the risk that a mild winter or high winds could snap the bunches off at the stalks.

There’s also no guarantee the ice will cometh. Not in Europe.

In Europe, the leading ice-wine nation, Germany, gave up on its eiswein harvest in 2006 and 2011. This is one reason why the nation that invented the category (by accident back in 1794 and then revived it in the 1960s) has relinquished its ice-king crown to Canada, where snowy winters are more certain. One Canadian winery, Pillitteri Estates, expects to produce 50,000 cases from its Niagara-on-the-Lake vineyards this year, after harvesting for several nights in a row.

It’s not just the harvesting that’s more difficult for ice-wine makers: The whole winemaking process is more complicated. Frozen grapes are much harder to press and it requires a lot more pressure to get a trickle flowing from the large pneumatic press. “It can take an hour for the flow to start,” Boris explains, and four or five hours to get the last drop.

The sugar-rich juice is also more difficult to ferment. Yeast cells like to gobble up sugar and to turn it into alcohol, carbon dioxide and heat, but they overdose in super-sugary must and die off quickly.

Boris’s ice wines usually ferment for a few months before the Bordeaux-sourced yeasts give up at 7-9% alcohol. What they lack in ABV, they make up for in price. Boris’s wines are in the €24-€40 range (for a 0.25L bottle), which is high for Croatian wines and similar to Canada’s prices (where the average for icewines is $45 for a half-bottle and the top end is $300). The price range for German eisweins is $20-$800, with €40 being fairly typical.

These price tags reflect the expense of producing such luscious elixirs. It’s not just the extra costs involved in protecting the berries from mould during the spring, summer and autumn and from birds during the winter, the volume of wine produced is tiny. It’s 8-15% of what a table wine producer could bottle from the same amount of land.

Boris currently has about 27,400 vines in 6ha of land (spread over five vineyards). Even allowing for the fact that many (4ha) of his vines are new (planted in 2012), his yield is very low. His annual output is about 3,500 bottles in a good year. That’s 3,500 x 0.25L bottles — the equivalent of about 1,100 ordinary bottles of wine. Other winemakers with 7,400 mature vines (planted 1998-2002) would expect to produce more than 11,000 bottles of wine a year.

It’s not easy to sell either, at any price. Very few people order a bottle of dessert wine in restaurants and even fewer knock back several glasses at home. Boris has consistently won awards since his first ice wine (the 2005 vintage) hit the market in 2008. In the six years that followed he bagged an impressive six gold, eight silver, six bronze medals and a Regional Trophy at the Decanter World Wine Awards in London and the 2009 was named among the world’s top 10 sweet wines, yet Boris does not currently have a distributor in Decanter’s home market, the UK. Appearances at wine fairs in London, Düsseldorf, Merano and Moscow have not secured regular international sales either. Most of his customers are restaurateurs in Croatia’s tourist towns, its capital Zagreb, specialist wine shops and visitors to the winery.

All of which leads some wine writers, such as Jancis Robinson, to question the point of ice wines. She said in 2002: “I am not 100 per cent certain that I think all the effort is worth it.”

But one drop of the nectar at Boris’s winery and I could see why no other wine satisfies him. It looks and tastes like liquid gold, except liquid gold is easier and cheaper to make. Unlike other dessert wines (such as Sauternes and Tokaji, the French and Hungarian sweet wines made from Botrytis-infected grapes), which have aromas and flavours reminiscent of honey, dried fruit and spices, ice wines still retain the delicate fresh fruity aromas and flavours of the grape variety — with complexity added by the long hang-time.

Typical aromas include stone fruits (such as apricot and peach), citrus fruits (especially grapefruit) and tropical fruits (such as mango, banana, pineapple and melon) while the flavours are stone fruits, mango and honey.

Unlike in Germany, where most eisweins are made from Riesling grapes, and Canada, where the most popular varieties are Riesling and Vidal Blanc, Boris makes his ice wines from eight different grape varieties: Chardonnay, Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc, Traminer, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Müller Thurgau and, coming soon, Yellow Muscat.

It’s quite an array and it’s interesting to see how the different varieties respond to this extreme treatment. I was particularly impressed with the ice wines made from Chardonnay and Pinot Blanc grapes. The debut Chardonnay from 2005 is so intense and complex that it disproves the widely-held view that ice wines don’t age as well as other dessert wines. At the other end of the spectrum, the Pinot Blanc from 2012 is so fresh, fruity and alive that it demonstrates the degree of nobleness that can be attained without rot. I’m obviously not alone in loving this wine, as it was awarded a silver medal at the International Wine Challenge 2014.

“Zagorje is an area usually bypassed by tourists unless they are driving from Zagreb to Slovenia or want to learn the history of humanity at the Neanderthal Museum in Krapina”

I was the first person to taste Boris’s latest releases — his 2012s — alongside his first efforts at his home and tiny winery in the small village of Hum na Sutli, in the Croatian Uplands, about 70km north of Zagreb. It’s a pretty area, with vineyards and farms on rolling hills. It’s an area usually bypassed by tourists unless they are driving from Zagreb to Slovenia or want to learn the history of humanity at Hrvatsko Zagorje’s main tourist attraction, the Neanderthal Museum in Krapina. It’s certainly an area overlooked by oenophiles. Once, when I asked a woman from Croatia’s Tourist Board about the wine there, she replied: “No, not good” and encouraged me to visit Plešivica, south-west of Zagreb.

Man has been growing grapes in Hrvatsko Zagorje for thousands of years. For many, the wines’ high acidity (often more than 10g/L) is too mouth-puckering, but for ice wines — with 100-350g/L of residual sugar — it’s the perfect foil.

Boris has been making wine seriously since 2002, starting with an auslese. He was introduced to ice wines at the Zorin winery in Slovenia in 2003, after stopping there on his way home from a wine fair. Inspired, he tried to make some ice wine in 2004 but the birds beat him to that harvest. But his first ice wine, the 2005 vintage, went on to win a gold medal, astounding many winemakers in Croatia who had never heard of his brand, Bodren (short for ‘Boris Drenški’).

The template for Bodren wines is the 2009 version, when the Pinot Blanc and Pinot Gris were picked at -22ºC. This golden-hued ice wine is perfectly structured and balanced, with fresh and alluring aromas and rich apricot flavours. The Bodren Icewine 2011 (featuring Pinot Blanc, Chardonnay and Riesling) won a gold medal at the International Wine Challenge 2014 and the 2012, a blend of Riesling and Pinot Gris, has very attractive hints of lemon-grass and white pepper.

Boris also makes some interesting trockenbeerenauslese (TBA) wines from Botrytis-infected grapes. The Chardonnay TBA 2010 won a bronze medal at the International Wine Challenge 2014 and the Riesling TBA 2011 picked up a bronze at the Decanter World Wine Awards.

It’s an amazing collection of wines and honours for a part-timer who has no formal training in winemaking. Boris, who works as an archivist at Croatia’s Ministry of Health, has learned from books, the internet, his own mistakes and phone calls across the border to one of Slovenia’s top sweet-wine makers, Jožef Prus.

“There aren’t any rules, not in winemaking. Every year is a new one”

For Boris it’s all about instinct and moments of inspiration. “There aren’t any rules, not in winemaking,” he told me. “Every year is a new one and the health of the grapes dictates everything else.”

He admits this hobby is currently “taking more than it is giving”, but Boris has plans to make it a proper commercial venture which he can run with his daughter, Monika, who has been studying oenology in Zagreb. The 20,000 new vines will enable them to make a full range of sweet wines, from late harvest/spätlese (kasna berba) to auslese (izborna berba), beerenauslese (izborna berba bobica), trockenbeerenauslese (izborna berba prosušenih bobica) and, of course, more eiswein (ledeno vino).

The plan is to make these in a new 1,500sq m winery with a tasting room, shop, restaurant and wine therapy centre. “I am keen on building a wine wellness facility to breathe new charm into this region,” Boris says. “I know that cosmetics and preparations from grapes and wines are getting increasing attention in the world, and why not then, I wonder, in Zagorje? People are afraid of new ideas, but not me.”

Such a centre would be complemented by accommodation in the shape of traditional Zagorje houses (called hiža).

It’s an ambitious plan. But so is making world-class wines in an acid-bomb area. So is making award-winning wines when you’re working at another job full-time. So is leaving bunches of Traminer, Yellow Muscat, Pinot Gris, Pinot Blanc and Chardonnay grapes on the vine for five months longer than most other winemakers.

Boris proves it can be done and he has already secured some EU funding for the €3m project and is currently seeking other potential investors and partners who would like to help make this dream a reality.

While he’s telling me of his plans, I’m savouring the long finish of wines made eight winters ago. I smile at the warm joy in my mouth. It’s a reaction Boris encounters a lot in his winery; it’s a reaction that spurs him out into the freezing cold in the middle of the night.

“When I see how happy people are when they are trying out my wine, I think: ‘Let’s get on with it, I can do it better and better’.”

“Let’s get on with it, I can do it better and better”

Ice wine and food

The normal food pairings for ice wines are fruity desserts, ice cream and sorbets. I tried Bodren’s ice wines with fruit and cheese and discovered they go amazingly well with blue cheese. The main criterion is that the wine should be sweeter than the food.

zagorje Wine road

Bodren is on the Zagorje wine road. Two other wineries on this road worth visiting are Bolfan and Vuglec Breg. These family-run wineries also have restaurants and accommodation.

The Sever winery in Klanjec is worth seeking out too, as it makes a little wine from a rare local grape variety called Sokol.